Thomas Chandler born 1779

|

Back to Group 18 |

Ian Peter Chandler, a descendant of Thomas, provided the DNA sample which established that his family belongs to genetic group #18. Ian has provided the following vignette of his family.

One of my high school examination certificate awards was in history. I am a doctor (pathologist) by profession, and I have served on the Royal Society of Medicine’s medical genetics committee in Britain for 8 years. Researching my family history and participating in DNA testing have proved an excellent way to combine these two interests.

In the summer of 2006 my father Jim (now sadly passed away) who lived in rural south-west England and didn’t own a computer, asked me to research his family tree. A brief period of research first took me to the now closed Family Records Centre in Clerkenwell in north London, which contained all of the heavy, dusty handwritten birth, marriage and death index ledgers of England and Wales from mid-1837, when registering those vital events became a legal requirement in Britain, onwards.

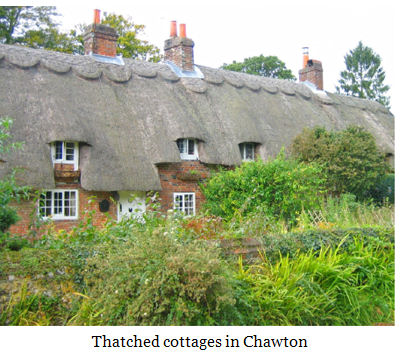

It also contained electronic scanned copies of the ten-yearly national censuses, so that one could see where one’s relatives were living, what their occupations were and the names, ages and birthplaces of children living at home. This mainly confirmed what my father and I already suspected, that my mid-nineteenth century Chandler family line comes from two villages in Hampshire in southern England called Chawton and Headley. Chawton will be recognized as home of author Jane Austen, of ‘Pride and Prejudice’ fame. Today it is a pretty, ‘chocolate-box’ commuter village of thatched cottages with a little school house and a big farm next to the church at the end of the main street.

It was a strangely spine-tingling, almost spiritual experience to stand outside the school house that my relatives must have attended, if for only a few years, to learn their reading, writing and arithmetic and then to walk down the road to the big farm which may have later provided their main source of employment as labourers.

By the time of the 1881 census my great-great-grandfather William, a gardener, was living in the Hampshire town of Aldershot with his wife Mary (née French) and two year old William junior. By 1891 there were five children – three sons and two daughters. William junior was my great grandfather and, according to his death certificate, he died of a diabetic coma in 1916 at his mother’s home in Aldershot at the age of 37. His employment was given as “fish hawker” (one who peddles fish).

William the fish hawker, father of three sons – James William, Herbert and Jock, died when James William, the eldest, was twelve. When their mother remarried and set up a new family, the three brothers were left with their grandparents, William (the gardener) and Mary Chandler.

Jock had a long, hard career in the Navy and never married.

Herbert died in 1933 at age 25. As a doctor, I was particularly struck by his death certificate. The narrative detail of the cause of death read “Uraemia following a fractured spine from a fall down a sewage shaft. Misadventure.” The accident had happened four months previously on 10th April and Herbert died on the 27th August. My heart went out to him and his family, a young man in the prime of life injured on a building site and lying paralysed in hospital for four months, probably fearing the worst before succumbing. The whole harrowing scenario was imaginable just from reading those twelve words.

James William was a baker, a “reserved occupation” during World War II, which meant he was not drafted. His only child, born 1942, was my father, Jim. I am also an only child, so this particular twig of the family tree is getting thin.

It also contained electronic scanned copies of the ten-yearly national censuses, so that one could see where one’s relatives were living, what their occupations were and the names, ages and birthplaces of children living at home. This mainly confirmed what my father and I already suspected, that my mid-nineteenth century Chandler family line comes from two villages in Hampshire in southern England called Chawton and Headley. Chawton will be recognized as home of author Jane Austen, of ‘Pride and Prejudice’ fame. Today it is a pretty, ‘chocolate-box’ commuter village of thatched cottages with a little school house and a big farm next to the church at the end of the main street.

It also contained electronic scanned copies of the ten-yearly national censuses, so that one could see where one’s relatives were living, what their occupations were and the names, ages and birthplaces of children living at home. This mainly confirmed what my father and I already suspected, that my mid-nineteenth century Chandler family line comes from two villages in Hampshire in southern England called Chawton and Headley. Chawton will be recognized as home of author Jane Austen, of ‘Pride and Prejudice’ fame. Today it is a pretty, ‘chocolate-box’ commuter village of thatched cottages with a little school house and a big farm next to the church at the end of the main street.