The reader may wonder how everyday letters were mailed between London and Leicestershire in the 1700s, and even more why such letters should have been preserved for so long; after all, the family was not titled, famous, or infamous.

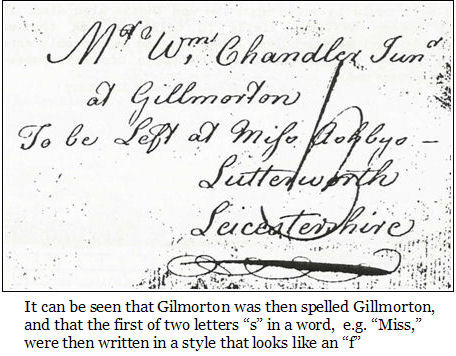

The first question is fairly easy to answer. There was a daily mail coach between London and Leicester, and this called at Lutterworth, a small market town near Gilmorton, and any packages were left at Miss Ashby’s shop for collection by farmers and others living locally. This is the way most letters were addressed: simply folded into a quarter and sealed.

This is the way most letters were addressed: simply folded into a quarter and sealed.

The reason why the letters were preserved is that they were held in a solicitor’s law office, first on a spike (the holes are still evident) and later in box files. These files were subsequently acquired by the Leicestershire Record Office and preserved. Before we discuss the reason for this legal involvement, it is necessary to set the scene.

Tony’s 5-times great-grandfather Simon (1709-1776) farmed Oak Farm, which still exists today. Then it was substantial, over 300 acres, and in addition Simon managed further acreage owned by his cousins Susannah, Anne and Alice, who were left without parents when still teenagers. Simon was churchwarden at Gilmorton for a few years. Most of the 60 letters were written to Simon’s brother William senior and his son William.

The map at right shows the counties of Leicestershire in the center of England and Sussex on the southern coast(both colored in blue) and London – all important locations to Group 8 in the United Kingdom.

Simon’s brother Edward was christened on 14 September 1712 at Ashby Parva, a small village adjacent to Gilmorton. He died at his home in Lambeth, now part of London, on 2 October 1781. He had taken his skills as a joiner to London and developed a successful business as an undertaker. He had invested the profits wisely in property and became a Freeman of the City of London. In 1774 Edward gave 600 pounds, invested in British Government Stock at 3%, for various Gilmorton parish charities, including the foundation of a school, named Gilmorton Chandler, to educate children within a Christian atmosphere. To put that in perspective, 600 pounds at that time would have paid a workman’s wages for 29 years. By the time of his death, he owned the following properties, mentioned in his five page will:

- 35 Fleet Market, London (undertakers business)

- 10 New Castle Street, St Sepulchre, London

- Warehouse and appurtenances thereunto belonging

- Estate comprising 13 messuages and tenements in New Castle Street

- Estate comprising 3 messuages and tenements in Sea Coal Lane

- Copyhold estate at Cold—— Hill, Aldenham, Middlesex (Aldenham was one of the richest areas in the entire country)

- Estates at Milk Street, near Chesham, Buckinghamshire

- Estate at Stanborough near Hatfield, Hertfordshire

- Messuage or tenement in Bell Yard near Temple Bar, London

- 32 and 33 Fleet Market, London with coach housing and stables

- 15 and 16 Sea Coal Lane

- Half share of George and Catherine Wheel public house, Bishopsgate Street, London

- 15 freehold houses in Kings Court and Anchor Alley, White Cross Street, St Luke parish, Middlesex

- 3 Walcot Place, St Mark, Lambeth

- 4 Walcot Place, St Mark, Lambeth

- Mortgage on land in Gilmorton

- Mortgage on premises in Old Street, St Luke, Middlesex

- Another 8 houses scattered around London, added as a codicil to the Will.

Using modern values, Edward was a multi-millionaire. His estate was very complex and there were many problems in the execution of his Will. This is believed to be the reason for a whole bundle of correspondence being preserved in a lawyer’s office.

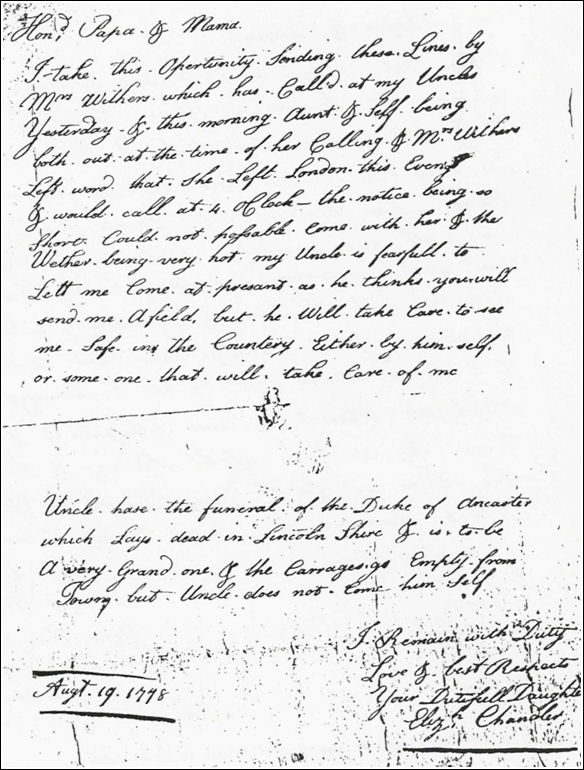

Letter from Elizabeth Chandler to her parents, dated 1778

(Transcription immediately below)

Transcription of Elizabeth’s letter:

This letter is from Elizabeth Chandler, fourteen year old daughter of Edward’s brother William, a farmer, and his wife Ann. Elizabeth was probably employed by her more wealthy uncle, who clearly was fond of the girl, concerned for her safety travelling home, and worried that her father would put her to work in the fields in the prevailing hot weather. The footnote tells a little of the type of client her uncle had. General Peregrine Bertie, 3rd Duke of Ancaster and Kesteven, who died on 12 August 1778, was Lord Great Chamberlain of England, Lord Lieutenant of Lincolnshire, and a member of the King’s Privy Council. Sending empty horse-drawn carriages 120 miles from London to Lincolnshire would have been an expensive undertaking!

In 1763 William and Ann Chandler, to whom this letter was addressed, sold the windmill above and the bank on which it stood near Gill Morton for 102 pounds and 10 shillings (present value 145,000 pounds or 230,000 US dollars). The windmill survived until 1915 when a severe storm was the final blow (apologies for pun) to its sails.

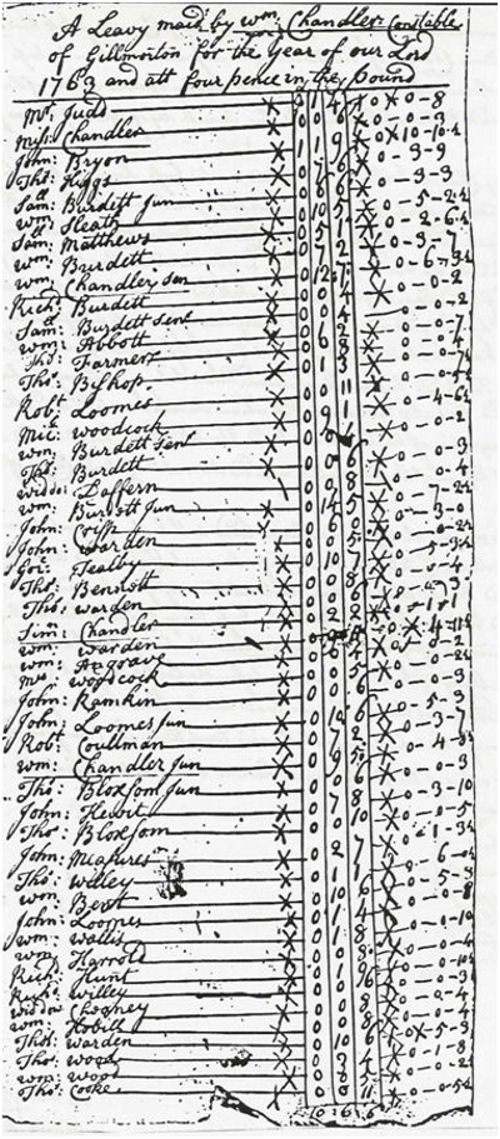

In the same year (1763), this William Chandler, being Constable of Gillmorton, was responsible for collecting the taxes imposed by the government of King George the Third. A record of his efforts appears below. It can be seen that there were four Chandler families living in the village at this time, all related. Other long established families- Burdett, Warden, Woodcock, Bloxsom and Tealby – all intermarried with various Chandlers over a period of about 100 years.