| Earliest known ancestor of Group 7C |

| Richard Chandler b. England 1575 d. Hampshire, England 1661 |

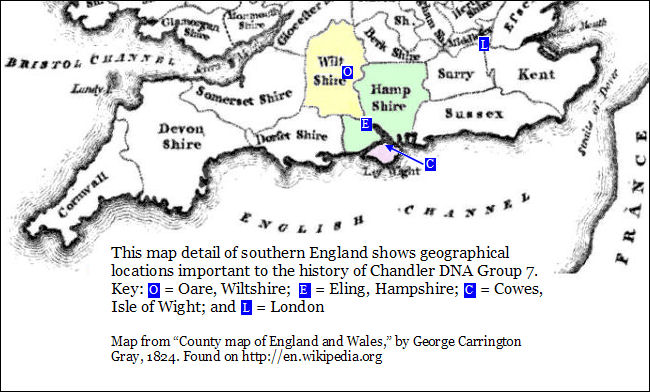

The largest group in the Chandler DNA Project has been designated Genetic Family Group 7. DNA test results place almost 100 participants in this group, the seventh such genetically connected family to be discovered by the project. It is believed the progenitor of all these participants lived in England; however, that common ancestor has not yet been identified. Consequently, based upon documented lineages from the year 1600 onwards, Genetic Family Group 7 has been divided into three subgroups: 7A, 7B and 7C.

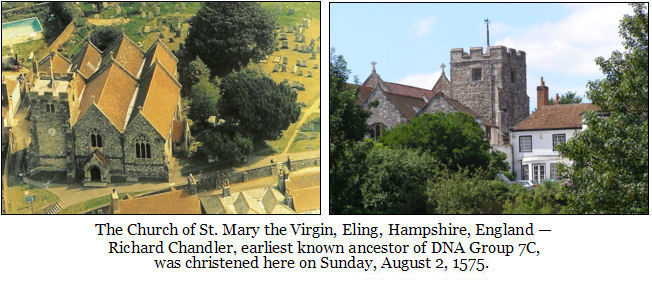

The earliest known ancestor of subgroup 7C is Richard Chandler, who was christened at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Eling (pronounced Ealing) in Hampshire, England, on Sunday, August 2, 1575. The names of his parents are not recorded in the register of St. Mary’s, spectacularly sited by its medieval builders atop Eling Hill. Indeed, although the registers began 37 years earlier, Richard’s entry in 1575 was the first Chandler appearance, suggesting that the family had recently moved to the area.

The names of his parents are not recorded in the register of St. Mary’s, spectacularly sited by its medieval builders atop Eling Hill. Indeed, although the registers began 37 years earlier, Richard’s entry in 1575 was the first Chandler appearance, suggesting that the family had recently moved to the area.

The DNA test results of a present-day descendant of Richard place him within the Group 7 family, but more closely associated with 7B, descendants of the Chandlers of Oare in Wiltshire, than 7A, descendants of John Chandler born 1600. Consequently he has been placed in a separate subgroup, 7C, and was its only member until May 2010. It was in that month that the DNA test results of an Irish Chandler made him the second participant placed in this genetic family. The two participants did not previously know of each other. The Irish Chandler’s ancestor was Richard, whose travels are described below, commencing with his enlistment on the British warship Spartan in 1819.

It is tantalizing that Eling, one of the largest parishes in Hampshire at that time, stretched to the Wiltshire border, and St. Mary’s itself is only about 30 miles south of Oare. So the closeness was not just genetic, it was also geographic. Readers could be forgiven for wondering why, then, we have not found the common ancestor of 7B and 7C. We must ask you to remember that the man we seek lived during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, if not earlier, and that records of ordinary people in that time were few and far between.

Richard was not a common forename among the genetically and geographically close 7B Chandlers of Oare, but whatever the origin of the name, certainly Richard’s christening in 1575 began a succession of 7C Richard Chandlers which continued for 250 years and, after several breaks, continues to this day.

but whatever the origin of the name, certainly Richard’s christening in 1575 began a succession of 7C Richard Chandlers which continued for 250 years and, after several breaks, continues to this day.

This does not aim to be a family tree of Group 7C or an account of the many Chandlers who would be on that tree. Rather, we aim to provide interesting facts about some of the members of the genetic family whose lives illustrate the progress of the family and the societies within which they lived. All of the Chandlers described below are 7C folk.

Eling, where Richard was christened in 1575, had strategic significance during the days of wooden ships. It has a natural outlet to the sea from which the timber for Britain’s navy and huge merchant fleet could be floated down the river to the royal dockyards at Portsmouth. In time, shipbuilding began at Eling itself. Later generations of Chandlers “married into” the shipbuilding and timber trades.

For the time being, however, the Chandlers of Eling were farmers. It is not known where their sympathies lay at the time of the Civil War which began in 1642, but it is unlikely they differed from the majority in that area, who were loyal to King Charles and the Royalist cause.

In 1645, at the end of the Civil War, there were three generations of Chandlers living in Eling: Richard Chandler senior, aged about 70, and his wife Christian; Richard Chandler junior, aged about 25, with his wife Elizabeth; and baby Richard born in December of that year.

Richard Chandler senior, aged about 70, and his wife Christian; Richard Chandler junior, aged about 25, with his wife Elizabeth; and baby Richard born in December of that year.

By the time the younger Richard was 16, he had lost his grandfather, father, mother and a sister and gained a widowed step-mother, Jane, and a half-brother, Henry. The great plague of 1665, much like the Civil War, largely passed Eling by, taking its toll on Southampton instead.

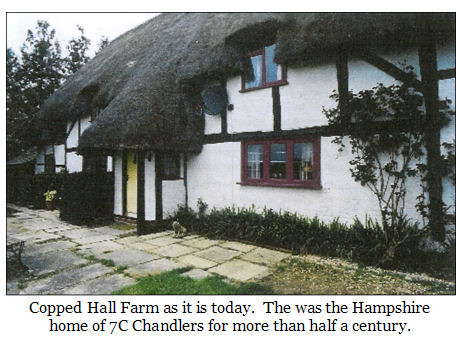

Jane, Richard and Henry became tenants of Copped Hall Farm in Winsor (not Royal Windsor, which lies in Berkshire) in the north of the parish of Eling, a quite modest south-facing two-storey timber-framed dwelling with a central chimney  containing two hearths.

containing two hearths. The building was, and still is, in an idyllic setting, then in 36 acres consisting of many separate strips of land – the inefficient method of farming in those days. The steep thatched roof of the farmhouse may explain the name Copped, as the word sounds similar to the Norman French for a high-roofed dwelling.

The building was, and still is, in an idyllic setting, then in 36 acres consisting of many separate strips of land – the inefficient method of farming in those days. The steep thatched roof of the farmhouse may explain the name Copped, as the word sounds similar to the Norman French for a high-roofed dwelling.

In 1670 Richard married Barbara Aysh or Ash of Millbrook, located across a tidal estuary from Eling. This would have been a dangerous courtship, as the quickest crossing of the water was by foot across a narrow causeway, the scene of many a drowning of unfortunates caught by the incoming tide in the pitch blackness of a moonless night. Their first child was named Barbara after her mother, a name that would echo down the centuries, as noted below.

located across a tidal estuary from Eling. This would have been a dangerous courtship, as the quickest crossing of the water was by foot across a narrow causeway, the scene of many a drowning of unfortunates caught by the incoming tide in the pitch blackness of a moonless night. Their first child was named Barbara after her mother, a name that would echo down the centuries, as noted below. It should be no surprise that their first son, born 1677, was named Richard.

It should be no surprise that their first son, born 1677, was named Richard. In due course this Richard married, and that couple produced another Richard born in 1717.

In due course this Richard married, and that couple produced another Richard born in 1717.

The last Richard born at Copped Hall was christened at St. Mary’s in Eling on April 15, 1737. He had a sister Elizabeth and four brothers, William, John, Arthur and Stephen.

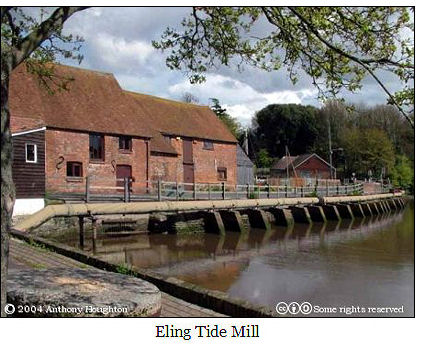

At a relatively young age, John took a lease on Eling Tide Mill from Winchester College, on condition that he renovate the mill at his own expense.

At a relatively young age, John took a lease on Eling Tide Mill from Winchester College, on condition that he renovate the mill at his own expense.

The mill operated by trapping the incoming tide in a mill pond behind a dam, then releasing the water through a gate onto the waterwheel. Each tide created about four hours of milling time. Grain was brought to the mill from the surrounding countryside; doubtless Richard would have also taken his grain to his brother’s mill. There was regular trade with the Isle of Wight: the mill could receive grain direct from ships. John’s lease also gave him the right to collect tolls on vehicles crossing the ancient causeway built across the valley of the River Test.

John’s lease also gave him the right to collect tolls on vehicles crossing the ancient causeway built across the valley of the River Test. The tide mill and toll booth can still be seen today.

The tide mill and toll booth can still be seen today.

The Richard of this generation married and had four sons, Richard (of course), Charles, James and John, and two daughters, Barbara and Elizabeth, during the 27 years he and his wife Elizabeth had together before she died in 1789. Soon after her death, Richard packed up and moved his family some 12 miles through the New Forest to its southern edge, near Lymington. The New Forest is a former royal hunting area appropriated in 1079 by William I (known as William the Conqueror).

Soon after her death, Richard packed up and moved his family some 12 miles through the New Forest to its southern edge, near Lymington. The New Forest is a former royal hunting area appropriated in 1079 by William I (known as William the Conqueror).

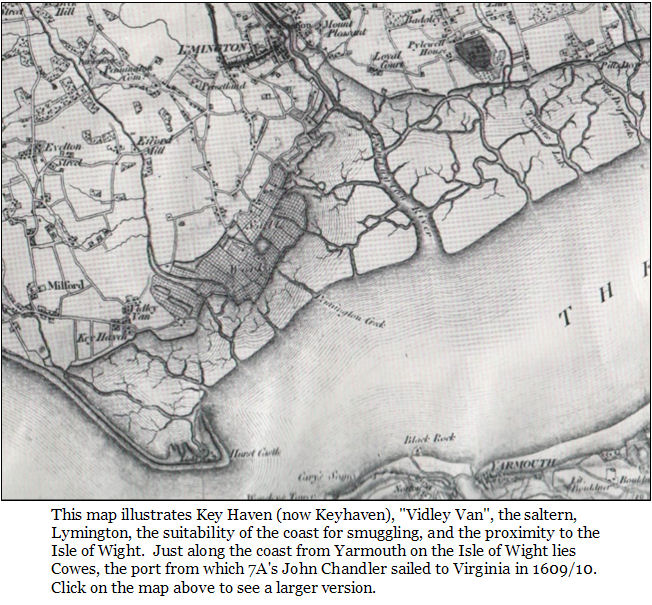

Richard’s brother Stephen became a prosperous farmer who married twice and later moved to the intriguingly named Vidle Van Farm near Keyhaven, which is only about five miles from his brother’s home at Lymington.

Stephen died in 1815, leaving the huge sum of seven thousand pounds (equivalent today to about five million pounds or eight million US dollars) to his second wife Sarah and son Stephen. When considering how this fortune might have been amassed, it should be noted that the blockades of the Napoleonic wars had reduced supplies and consequently increased farmers’ profits.

(equivalent today to about five million pounds or eight million US dollars) to his second wife Sarah and son Stephen. When considering how this fortune might have been amassed, it should be noted that the blockades of the Napoleonic wars had reduced supplies and consequently increased farmers’ profits.

Another possible clue to the source of Stephen’s affluence lies in the name of his farm, Vidle Van: possibly a corruption of the French vide le vin, which could be interpreted as ‘unload the wine’. The name was recorded as Vidlievan in the year 1606. The marshy coastal area where Stephen lived was a haven for many smugglers, and his property was conveniently located on a navigable creek. The French coast lies 70 miles to the south, across the English Channel. Another possible source of Stephen’s income was salt, a vital commodity. There was certainly a saltern on Vidle Van Farm at one time. Sea water was allowed to enter through sluice gates and then trapped, and salt was obtained from it by evaporation and then by boiling the concentrated brine. Perhaps Stephen became prosperous by a combination of being a hard working farmer, with possible sidelines of salt production and a little smuggling.

Another brother, William, did not fare as well as his siblings. He became “reduced in circumstances” and received charity for many years until his death at the age of 80. Stephen provided a weekly allowance of one pound to his brother, who had six children to rear, three of whom would become seafarers.

who had six children to rear, three of whom would become seafarers.

Richard’s home about two miles outside Lymington was East End Farm, about one and a half miles from the coast and right on the edge of the New Forest. The farm enjoyed ancient forest rights, allowing Richard to keep 7 horses, 15 cows and 21 pigs and to cut peat from the heath for fuel and wood from the forest. In 1791 Richard the elder married for a second time at Boldre, two miles from his farm.

In 1791 Richard the elder married for a second time at Boldre, two miles from his farm. The bride was also widowed, and both were in their mid-fifties. Three months later, the younger Richard married in the same church.

The bride was also widowed, and both were in their mid-fifties. Three months later, the younger Richard married in the same church. He moved to nearby South Baddesley and became a shopkeeper. The elder Richard became deeply involved in charitable work for the poor, and there was only one year in the period 1799 to 1809 when he was not appointed as overseer of the poor.

He moved to nearby South Baddesley and became a shopkeeper. The elder Richard became deeply involved in charitable work for the poor, and there was only one year in the period 1799 to 1809 when he was not appointed as overseer of the poor. He died in February 1810.

He died in February 1810.

A remarkable record exists of the younger Richard’s family in South Baddesley in 1817, because Henry Comyn, curate of the local church, kept notebooks detailing every parishioner, in preparation for a new incumbent curate. Richard was running his shop with his wife Edith. Their eldest son Jacob had gone to live in London, middle son Richard was described as a seaman (see below), and Philip, the youngest, was still at home. There were only eleven families in South Baddesley, yet there was another shop.

There were only eleven families in South Baddesley, yet there was another shop. This suggests that the village served a large area, perhaps the whole of the southern part of the New Forest, and it is likely that Richard’s shop (the building still stands) was a general store with a wide range of merchandise.

This suggests that the village served a large area, perhaps the whole of the southern part of the New Forest, and it is likely that Richard’s shop (the building still stands) was a general store with a wide range of merchandise.

The rural life that the previous Richards had enjoyed was fast disappearing. There was a mass exodus of young people from the countryside to the cities, and our family was no exception. Philip would join his brother in London, and Richard would take to the high seas.

As mentioned previously, three of Richard’s first cousins were already seamen. One of them fought in the greatest naval battle of all time, the Battle of Trafalgar, aboard the Royal Sovereign, the first ship to engage the enemy. Another died aboard a Man of War at Port Royal, Jamaica. Family gatherings must have been seasoned with tales of exotic lands and high adventure. Richard volunteered in Cork, Ireland, in 1819.

Another died aboard a Man of War at Port Royal, Jamaica. Family gatherings must have been seasoned with tales of exotic lands and high adventure. Richard volunteered in Cork, Ireland, in 1819. The day after his enlistment, along with the rest of the company of the Spartan, he was required to witness three floggings for bad behavior: two men received 12 lashes, and one, for theft, 35 lashes.

The day after his enlistment, along with the rest of the company of the Spartan, he was required to witness three floggings for bad behavior: two men received 12 lashes, and one, for theft, 35 lashes. A sobering introduction, and a regular experience.

A sobering introduction, and a regular experience.

In the spring of 1820, the Spartan delivered medical supplies to a squadron in Rio de Janeiro. In May she was moored off Barbados.

In May she was moored off Barbados. More floggings there, as on most sailing ships at that time. After a few months at home, Spartan sailed again to the West Indies. After some time at Barbados and Jamaica, Spartan returned home and Richard was discharged,

More floggings there, as on most sailing ships at that time. After a few months at home, Spartan sailed again to the West Indies. After some time at Barbados and Jamaica, Spartan returned home and Richard was discharged, as was the custom, then immediately mustered in February 1821 on the Pyramus, a 36-gun frigate with 264 men.

as was the custom, then immediately mustered in February 1821 on the Pyramus, a 36-gun frigate with 264 men. Richard must have got some shore leave, because he took a wife, Elizabeth, in Plymouth,

Richard must have got some shore leave, because he took a wife, Elizabeth, in Plymouth, and there is considerable evidence that she sailed with him (not an unknown occurrence) on the Pyramus on a lengthy tour of duty to the West Indies. After two years, plague had taken so many men that Richard was promoted to Gunner’s Mate.

and there is considerable evidence that she sailed with him (not an unknown occurrence) on the Pyramus on a lengthy tour of duty to the West Indies. After two years, plague had taken so many men that Richard was promoted to Gunner’s Mate.

Two remarkable entries in the parish register of Port Royal, Jamaica, on September 21, 1823 and October 3, 1824 record the baptisms of Richard and John respectively, both sons of Richard Chandler, Gunner’s Mate, HMS Pyramus and Elizabeth his wife. The dates of birth were February 3, 1822 and March 21, 1824, respectively.

After more than three and a half years in the West Indies, Richard was discharged and sent home aboard the Serapis, a hospital ship. Richard and Elizabeth returned to Hampshire in 1825. Elizabeth died in childbirth in 1827. Richard remarried in 1832 and spent the rest of his working life ferrying mail from Lymington to Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight. He died in 1848.

Richard and Elizabeth returned to Hampshire in 1825. Elizabeth died in childbirth in 1827. Richard remarried in 1832 and spent the rest of his working life ferrying mail from Lymington to Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight. He died in 1848.

The squalor and danger of life in rapidly growing London must have been an awful shock to young people brought up in rural Hampshire. The only redeeming factor was employment. Jacob and Philip got jobs as warehousemen working for the largest trading company in the world at that time – the East India Company. They raised families and were joined by Chandler cousins who drifted into London and sought their help in finding work. Labourers, laundresses, washerwomen, coal heavers, shoemakers, butchers, carpenters, cow keepers, farmers, cab drivers: these were the occupations of the people whose lives were thrown into turmoil by what was intended to be an act of kindness 32 years previously.

They raised families and were joined by Chandler cousins who drifted into London and sought their help in finding work. Labourers, laundresses, washerwomen, coal heavers, shoemakers, butchers, carpenters, cow keepers, farmers, cab drivers: these were the occupations of the people whose lives were thrown into turmoil by what was intended to be an act of kindness 32 years previously.

Elizabeth Chandler, widow of Stephen Chandler the younger who died in 1826 at the age of 45, finally succumbed to cancer in 1858. Stephen had stipulated in his will that a sum of eight hundred pounds of his four thousand pounds estate (multiply all values by 680 to assess current value) was to be divided equally among all his first cousins on his father’s side. The money, however, was to be held in trust and not distributed until six months after the death of his widow. In the event of the death of any or all of the first cousins, the money was to be divided among their children. Because of its complexity, the trust in Stephen Chandler’s will was referred to the Court of Chancery, widely known for its bureaucracy and delay.

To cut short a very long story, the 800 pounds had increased with interest to 825, but then reduced to 761 by bank charges. Nothing new there. Tax took 37 pounds, and legal costs another crippling 434 pounds. Nothing new there either. Instead of the residue of 290 pounds being divided among the 37 claimants, it was first divided into eleven “parcels” of 26 pounds plus change, corresponding to the eleven first cousins who had surviving children. Then each parcel was subdivided among the children of each deceased first cousin, with the result that an only child received six times as much as one who had five siblings. The largest legacy was twenty-six pounds and change; the smallest, four pounds and change. One thirty-seventh of 800 pounds would have given each claimant almost 22 pounds (15,000 pounds or 21,500 US dollars in today’s terms). This would have been a welcome sum to those experiencing hard times. Instead, a harsh world reduced the long-awaited inheritance for most of them to a meagre fraction of what they had probably anticipated with their relatives for years.

And now we will hear the echoes down the centuries. In 1942 in wartime Britain, another Barbara Chandler lived in rented rooms on the top floor of a house in Clifton, part of the port city of Bristol. Her husband Leonard, known as Peter, who had been a telephone lineman in peacetime, was away serving with the Royal Signal Corps. An enemy bomber, probably aiming for the adjacent hospital or the nearby broadcasting studios of the BBC, dropped a bomb which went through the roof and stopped, without exploding, with its nose in Barbara’s bathroom. Heavily pregnant, Barbara grabbed her seven year old son Michael and rushed from the house. Minutes later, the bomb exploded, totally demolishing the house.

Barbara, left with no furniture, rented rooms in the attic of a house owned by the local church. A few weeks later, on 30 November 1942, she gave birth to her second son. Although she knew nothing of her husband’s family history, she named the boy Richard and, in honor of their wartime leader, who shared the same birthday, gave him the second name Winston. The boy Richard was christened, like his ancestor 367 years previously, in a church dedicated to St. Mary the Virgin. He later sang in the choir of that church, from which his home was rented.

Although she knew nothing of her husband’s family history, she named the boy Richard and, in honor of their wartime leader, who shared the same birthday, gave him the second name Winston. The boy Richard was christened, like his ancestor 367 years previously, in a church dedicated to St. Mary the Virgin. He later sang in the choir of that church, from which his home was rented.

Barbara and Leonard divorced when Richard was eleven, and this was the last time the brothers saw their father or any member of his family. Barbara herself was an only child, so Michael and Richard had a very small extended family. Both boys did quite well at school and in business life, which took both of them to work in different countries for a number of years – they seemed to have an innate willingness to travel and explore new horizons. Perhaps because of their parents’ circumstances, neither had an interest in family history. In later years, Richard (now universally known as Dick, except by his mother when he was in trouble, and later by his wife for the same reason) began to explore the ancestry of his step-children. Like many others he soon became addicted to the thrill of genealogical detective work and the pleasure of helping others to break down brick walls. Still disinterested in Chandler family history, he joined the Guild of One-Name Studies to help with the research on his step-children’s forebears.

Several years later, the Guild member who had been researching the Chandler name had a stroke and was unable to continue his study. The Guild asked Dick to take over the Chandler study in addition to his own and, thinking ahead to impending retirement, he agreed to do so. Still disinterested in his own lineage, Dick helped hundreds of people around the world with their Chandler family history. While still living in England, he was contacted by Joe Chandler of the Chandler Family Association to try to determine the English origins of John Chandler born in 1600. Soon after the Chandler DNA project began, Dick participated and, to everyone’s surprise, his results showed a kinship match with Group 7. Only then did he begin to explore the earlier generations of his own lineage. What a succession of coincidences led this Richard Chandler – son of Barbara, nearly not born at all due to a German bomb, christened at St Mary the Virgin, carrying this DNA fingerprint, genealogically inactive for nearly 60 years and then becoming active with Chandler surname research internationally – to come to the notice of Joe Chandler. You wouldn’t bet on it.

This summary, produced by (at that time) CFA President Dick Chandler, who at this time, lived in Canada, is in large part a condensation of a 130-page book written by Dick’s 7th cousin Glenn Chandler, a successful researcher, author, novelist and script writer of the popular British TV series “Taggart”. Glenn was named after big-band leader Glenn Miller, who was greatly appreciated by Glenn’s musician father.

1 Baptism Register, St. Mary the Virgin, Eling, Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

2 Baptism Register, Holy Cross, Wilcot, transcript by Wiltshire Family History Society.

3 Baptism, Marriage and Burial Registers, St. Mary the Virgin, Eling – Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

4 Hearth Tax Returns, Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

5 Recent owners of Copped Hall Farm.

6 Marriage Register, Holy Trinity, Millbrook, Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

7 Baptism Register, St. Mary the Virgin, Eling, Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

9 Baptism and Marriage Registers, St. Mary the Virgin, Eling, Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

10 Baptism Register, St. Mary the Virgin, Eling, Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

11 Records of the Manor of Eling, Winchester College Archives.

12 The Rarest Tide Mill by David Plunkett, //elingexperience.co.uk, last updated November14, 2025.

13 Records of the Manor of Eling, Winchester College Archives.

14Baptism, Marriage and Burial Registers, St. Mary the Virgin, Eling, Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

15 Records of Wills, Hampshire Records Office, Winchester.

16 Records of the Consistory Court of Winchester – Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

17 New Forest Commoners AD 1792 (F.20/51), UK National Archives, Kew.

18 Marriage Register, St. John the Baptist, Boldre, Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

20 Boldre Overseers’ Accounts and Churchwardens’ Books, Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

21 Burials Register, St. John the Baptist, Boldre, Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

22 “Comyn’s New Forest” 1817 Directory of Life in the Parishes of Boldre and Brockenhurst, edited by Jude James, published using the original notebooks kept by the Reverend Henry Comyn.

24 Trafalgar Ancestors, UK National Archive.

25 Master’s Log, HMS Spartan, UK National Archives, Kew.

30 Master’s Log, HMS Pyramus, UK National Archives, Kew.

31 Pay Book of HMS Pyramus, UK National Archives, Kew.

32 Master’s Log, HMS Pyramus, UK National Archives, Kew.

33 Parish Records, Port Royal, Jamaica, extracted by LDS Church.

34 Royal Navy Records, UK National Archives, Kew.

35 Burials Register, St. John the Baptist, Boldre, Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.

36 Parish records of Southwark, Southwark Local Studies Library, Borough High Street, London.

37 Affidavits collected by solicitors during the Chandler Chancery Case of 1859, UK National Archives, Kew C31/1400-1403 and Hampshire Record Office, Winchester 4M92/N95/3/.

38 Oral information supplied by Barbara Chandler.

39 Certificate of Registration of Birth, Bristol Register Office.